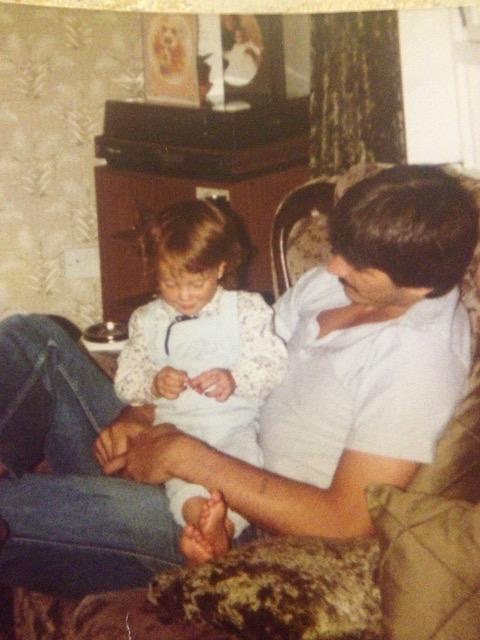

There’s a photograph taken on my third birthday that I treasure. I’m sitting on my father’s lap, lost in chatter, and he’s gazing adoringly at the little auburn-haired toddler in dungarees and bare feet. Photographs from this time are scarce; even fewer feature me with my dad. As my mum euphemistically puts it, there was “a lot going on”.

By the time I turned three, Dad had been on strike for five months. There was little time for happy family snaps; there were mouths to feed and heads to keep above water. Plus, paying to develop films was a luxury my parents could ill afford. So, this picture – taken in August 1984 – is rare and precious. In that frame, time stands still.

I still wonder what was on my dad’s mind that day. His face betrays no clues; he looks like any doting father, absorbed in his little girl’s babble. I can’t ask because cancer took him in 2003, so I rely on my mother – the photographer – for her memories. I know he took the day off from his cash-in-hand decorating gig to spend my birthday at home. I see a man trying desperately to be a good father in the middle of a metaphorical storm. It’s the first picture I showed my son of the grandfather he never met.

I imagine a family celebration felt like a rare reprieve when the reality of the strike – and what it meant for us – was dawning on my parents. Mum found out she was expecting my twin sisters around that time, and even today, when she talks about it, her voice is tinged with sadness. What should have been an exciting time for a young couple – her twenty-two, him twenty-six – was filled with dread.

Already struggling financially, they had no idea how to provide for two new additions. How could they revel in the joy of new life when we relied on food parcels from the union? How would we survive as a family of five?

My parents did all they could to keep the wolves from our council house door. The cash dad earned from decorating didn’t stretch far, so my pregnant mum supplemented our income by catering weddings and selling loft insulation.

My Grancha Tom provided free childcare, and I spent so much time shadowing him around his allotment that I started calling him “dada”. When he needed a break, my actual dad would take me to the picket line, wrapped up warm in my buggy. I think I remember those trips to Six Bells Colliery, although I’m unsure if it’s an invented memory, embellished with every family telling.

They say it takes a village to raise a child; ours in the Gwent valleys helped raise this one. From food parcels to hand-me-down clothes, everybody mucked in. Aunties (biological and the valleys kind), neighbours and strangers showed solidarity through kindness, even when they had little to give.

It’s the community pulling together that my mum remembers the most. But she also talks of unexpected fractures. One of my dad’s friends started driving strike breakers into work, and they never spoke again. Another colleague who crossed the picket line had such a hard time he emigrated to Australia.

My parents were tired, stressed and pregnant, but they were a team. It felt like Thatcher was waging a very personal war against them sometimes, and they were adamant she wouldn’t win.

As for what I remember, the truth is very little. British children raised during the 1940s, if they were lucky, don’t remember bombs and bullets. Instead, they recall the more mundane features of wartime life, like ration books and gas masks. For this child of the strike, it’s not picket lines or bin fires that I remember, but the potatoes my nan brought us every week. They filled our bellies quickly and cheaply, putting me off mash for life.

Spuds (in all their forms) and the contextless, strange-sounding word “Scargill” became seared on my tiny brain. TV news beamed conflict and shouting men into our living room every night. I was too little to understand what was happening, but I soaked up the stress and tears at home.

As weeks turned into months, my parents sold their car, and dad bought a cheap motorbike. My mum dreaded an accident, but he needed a vehicle, so she swallowed her fear. If anything happened, it would be yet another thing to blame that damn woman for.

Mum managed the meagre household budget to the penny and made sure dad paid his subs so he could play rugby every Saturday. Garndiffaith RFC gave the strikers drink tokens, like free school meals for working-class men. “It was important for his mental health,” she explains now, but that’s not the term they used back then. She didn’t have the language for why Saturdays – his weekly chance to exercise and socialise with his friends – were non-negotiable. But it meant he could forget the struggle for a while. Could she ever forget, though?

When the longest and most acrimonious industrial dispute in modern British history ended, Mum was a month away from giving birth to my sisters. It felt like a crushing weight on her chest evaporated. But it was a temporary reprieve.

My dad was one of over 140,000 miners who went out on strike. For him and many others, it was the beginning of an end. In 1988, Six Bells closed for good.

The scars run deep in former mining communities like ours, both on the landscape and the collective psyche. Those 362 days were a political awakening for my parents (and for me, by osmosis). We all became campaigners in different ways; our socialist values forged in the furnace of that not-quite-a-year.

Four decades on, I’d give anything to hear dad rage about that damn woman again. Like my treasured third birthday snap, the strike is a moment frozen in time. Yet, it remains alive in me. I carry it with me, always.

Leave a comment